Some things are just disgusting. For the most part, we agree on what those things are. For instance, we don’t like others’ bodily fluids, and we don’t like decaying meat. Most of us are disgusted by crawling insects, too. Psychologists believe that the emotion disgust evolved as a protective device against substances that might be harmful if ingested.

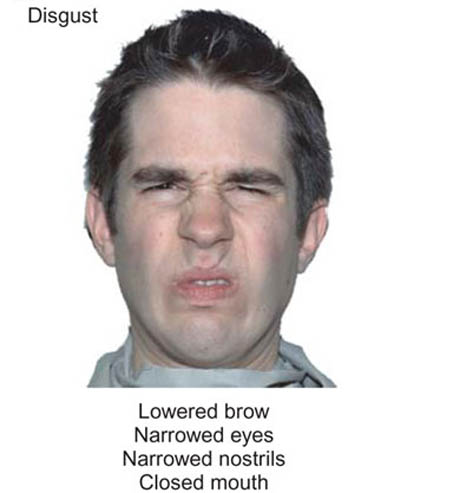

Disgust is displayed on the face in the same way universally. We all show it the same way.

It seems, however, that our sense of disgust may sometimes affect how we think about what we want and don’t want in ways that we are not normally aware of. Researchers Andrea Morales and Gavan Fitzimmons devised a clever way to test this. In their series of experiments, the researchers placed a number of items in a shopping cart, then asked participants in the experiment how much they would be willing to pay for one of the items. Among the items, one was a package of cookies and one was a package of feminine napkins. Both were in sealed packages, just as you would find them in a store.

In the experiment, for half of the participants the package of feminine napkins was touching the package of cookies in the shopping cart; for the other half, the two packages were separated by six inches. After viewing the shopping cart, participants were asked to say how much they would like to try or use the products in the shopping cart. What the researchers found was that participants who had seen a cart in which the cookies and the feminine napkins were touching rated the cookies as significantly less desirable than those who had seen the cart where the two were not touching. This effect disappeared, however, when researchers used a package of cookies that was opaque.

In other words, people acted as if the cookies had been contaminated by touching a sealed package of feminine napkins, but only if the cookies were in a clear package.

To test the effect further, the researchers conducted the same experiment, but substituted a package of lard for the feminine napkins, and a package of rice cakes for the cookies. Half the participants saw the lard touching the rice cakes, half saw the lard in the cart but not touching the rice cakes. Researchers then asked participants to rate the fat content of the rice crackers. Lo and behold, participants who had seen the two products touching rated the rice crackers as containing more fat!

Certainly, we all know that a sealed package of feminine napkins could not “contaminate” a sealed package of cookies, and that a package of lard could not make a package or rice crackers more fattening. Certainly, we are rational creatures and these are not rational thoughts.

But whether we like it or not, we are influenced by many non-rational thoughts.

At BeyondThePurchase.Org we are researching the connection between people’s spending habits - how do you spend your money and who do you spend it on - and social emotions. To learn about your spending habits, how much you experience prosocial emotions, and how you define the good life, first Login or Register with Beyond The Purchase, then take a few of our spending habits surveys (Experiential Buying Scale, Materialistic Values Scale, and Compulsive Buying Scale), our Dispositional Positive Emotion Scale, and our Beliefs about Well-being. We think you may learn a lot about what causes you to part with your hard-earned money.

This blog post was written by Kerry Cunningham, a graduate student in the Personality and Well-being Lab at San Francisco State University. Follow @kerryfc

The research discussed above was based upon research published as: Morales, A., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2007). Product contagion: Changing consumer evaluations through physical contact with “disgusting” products. Journal of Marketing Research, 44, 272–283.